Strengthening monitoring and metrics for just transitions in emerging economies

In emerging economies, for metrics to play an effective role in driving progress for both the net zero transition and social justice, monitoring needs to get closer to the ground. Here, Rob Macquarie and Judith Tyson explore what it takes to go beyond high-level talk about climate finance allocation and use national and domestic policy frameworks to track how climate transitions ‘walk the talk’ on just transition.

Climate finance is interdependent with approaches ‘closer to the ground’

Many emerging economies face twin challenges related to the net zero transition — the economic transformation required to adopt green technologies and the challenge of building resilience against escalating climate vulnerability.

Low-income and lower-middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs) in particular face multi-dimensional challenges, including physical climate risks, social disruption from transition dynamics, loss and damage, scarce institutional resources, and — crucially, for the Just Transition Finance Lab — a lack of finance, all of which are undermining progress towards a just transition.

Some countries have argued at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Just Transition Work Programme that adequate climate finance is inseparable from just transitions. Yet the finance required to power transformation or build resilience is unique to each geography. In leading emerging economies, climate innovation is booming, with the private sector delivering new solutions — for instance, Brazilian multinationals powering electric engineering and Indian companies advancing innovation in green hydrogen, green steel and electric vehicles.

However, elsewhere climate adaptation challenges are acute and face insufficient finance. With the multilateral discourse focusing on global contributions, there is less attention to local needs and action such as support for vulnerable groups of informal workers and marginalised communities. For transitions and resilience to be just, it is important to recognise the diversity between and within countries and connect finance to the real missions in specific places, sectors and communities.

In other words, to mobilise finance for just transitions, getting ‘closer to the ground’ is key. In this commentary, we focus on how monitoring and metrics can contribute to this goal.

How to get effective ‘closer to the ground’ monitoring and metrics

The high-level dialogue about allocations has played a vital role in agenda setting, acting as a mechanism to close financing gaps by leveraging private investment at scale. But this debate needs to now move to action and connect with domestic and corporate governance, to enable the momentum towards the transition target in the places where finance is flowing.

That means finding greater nuance in monitoring and metrics and enabling their integration into finance for a just transition in emerging economies and LMICs. The G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group (SFWG), which included ‘assessing and mitigating negative social and economic impacts’ as one of the five key pillars of its 2022 Transition Finance Framework, last year recommended deepening the implementation of transition planning and improved metrics.

Public policy frameworks for monitoring, evaluating and learning (MEL) on just transitions can be a key aspect of this. A comprehensive guide from the Initiative for Climate Action Transparency (ICAT) and the World Resources Institute (WRI) sets out steps for countries to take.

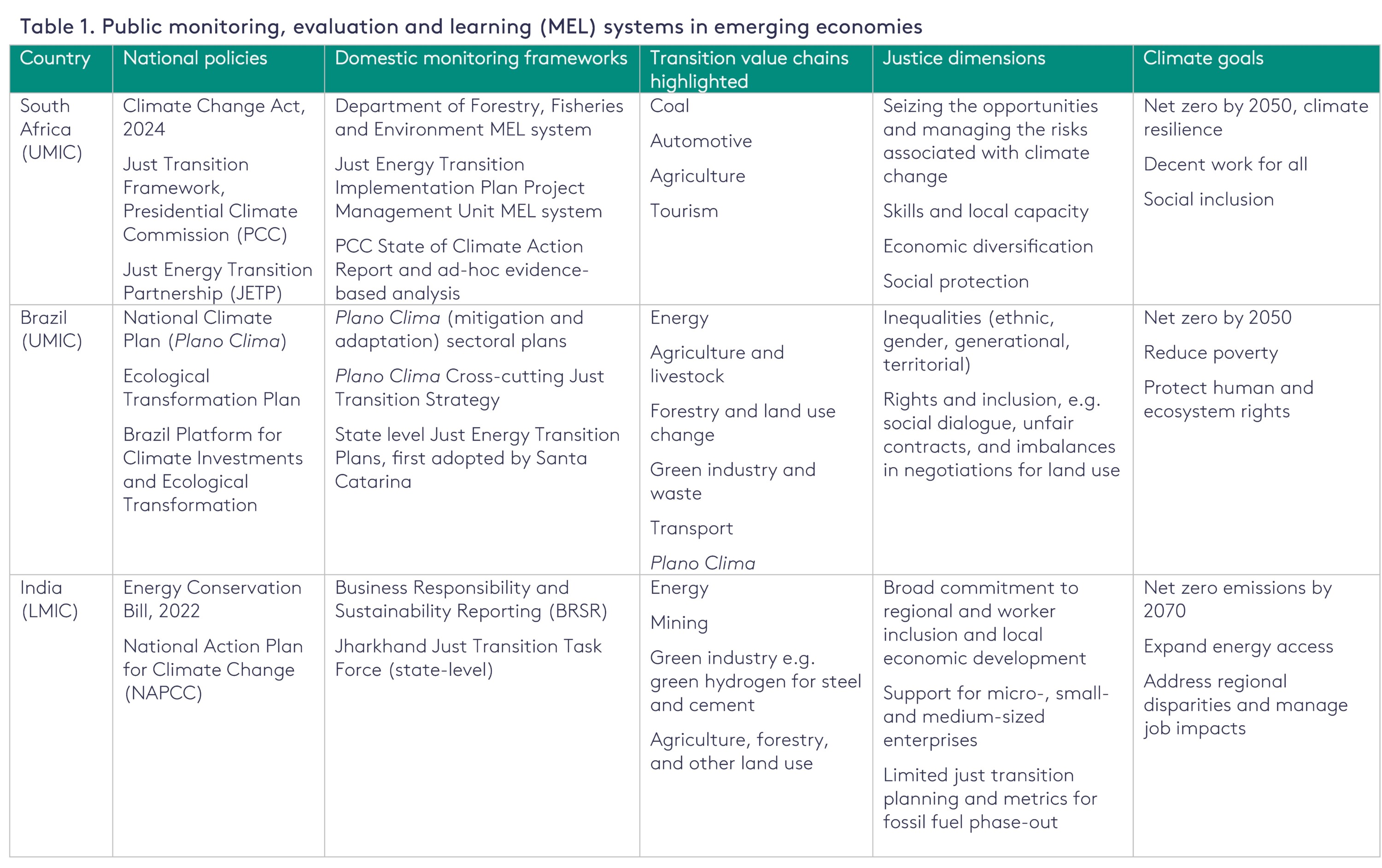

Leading examples exist in both upper- and lower-middle-income countries (UMIC and LMIC), including South Africa, where several intersecting, public MEL systems have been created to operationalise different aspects of the country’s just transition process. Brazil’s national Climate Plan (Plano Clima) features sectoral just transition goals and measures, a framework for monitoring the anticipated social impacts, and provisions for multistakeholder governance. Nigeria is building a ‘just and gender-inclusive transition monitoring, reporting, and verification framework’ to assess progress towards targets such as the equitable participation of women and youth in climate-related projects by 2030.

Domestic regulation and monitoring frameworks in developing countries are also important to ensure accountability and fairness. The Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR) framework in India and bespoke frameworks for just transition investments like TIPS’ Just Transition Tagging Tool for South Africa provide examples.

Table 1 outlines the nature of the transitions facing three of these emerging economies and how they are responding with relevant policy and regulatory instruments.

Multilateral development banks are also establishing ‘just transition indicators’ as part of their common approach to measuring the results of climate finance, providing examples of emerging best practice for others to build on. As highlighted in our recent research, monitoring of private companies’ just transitions can lead to more private investment with positive outcomes for people.

There are also early signals of collaboration between providers and recipients of finance to improve monitoring. For instance, South Africa launched a ‘JET Grants Register’ under its Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), drawing on support from international donors and dialogue with civil society groups. Indonesia, too, undertakes grant mapping for its JETP. By improving transparency of climate finance flows, their impacts, and their sources, such initiatives contribute to several dimensions of justice.

What else is needed?

While progress is clear, challenges remain. These include a “lack of sufficient financial incentives” and a “lack of relevant capacity [which] may lead to insufficient or ineffective implementation” (according to the G20 SFWG). Weaknesses in local data availability and impact analysis pose barriers to using data points and frameworks drawn from international monitoring approaches.

We suggest the following three priorities for decision-makers to deepen ongoing national efforts, international initiatives and partnerships, and the negotiations at Conference of the Parties (COP) 30.

- Build international networks to share transition learning and understand interconnected social impacts. UMIC, LMIC and LIC country stakeholders are affected by the actions of companies owned or headquartered elsewhere, especially in the Global North. Independent initiatives and official bodies can establish information pipelines to ensure that accountability and the attribution of risks (and benefits) reach across borders. Sharing information can be good for economic stability by refining standards, improving company data, and driving better investment decisions.

- Encourage deeper exchanges between investors and monitoring institutions on the timing, quantity and nature of information to help mobilise private investment. As well as domestically, these links can also be international. For example, country platforms in developing countries could improve engagement with international investors to mobilise private finance and there could be further coordination forums such as the recent initiative between the UK Government and the City of London. Investors committed to identifying transition risks and opportunities in their portfolios can engage directly with rightsholder groups through, for example, a community of practice models.

- Build local capability in social dialogue. It is easy to demand that rightsholders have a stronger voice in their specific contexts as well as through high-level policy dialogues, but it is hard to operationalise in practice. Adequate finance needs to be applied to building capacity for stronger social dialogue and real engagement with informal workers and marginalised communities. Improved metrics and understanding are needed to enable this. Important steps to promote this also include setting out clear protocols for strong engagement with grassroots community organisations and representatives and providing funding to support communities who lack the legal and technical resources needed to engage with companies on an equal footing.

In conclusion, while progress is being made, more needs to be done to deepen monitoring and metrics and their integration into finance for a just transition in developing countries. Most critically, we see a need for greater integration of rightsholders in these contexts, especially in LMICs and LICs, and in all developing countries where informal workers and marginalised communities are facing the gravest climate vulnerability with the least resources and capabilities to build resilience. More focus — and practical implementation — to ensure ‘no one is left behind’ is needed, and should take priority as countries collectively build an inclusive agenda for COP30.

The authors are grateful to the organisers and attendees of the Global Workshop on Monitoring Just Transitions in Cape Town, February 2024, hosted by ICAT, WRI, and South Africa’s Presidential Climate Commission. This commentary draws on participant contributions and feedback, including during a session the Lab co-organised with the World Benchmarking Alliance, on integrating the private sector and private finance into just transition monitoring.

The authors also thank: Laudes Foundation for engaging the Lab with their other grantee organisations; Rowan Conway and Sarah King for providing review and comments on a draft; Cara Hartley and representatives of three South African entities with MEL systems for sharing findings from an article forthcoming in the African Evaluation Journal; and members of a Private Sector Just Transition M&E discussion group, for sharing perspectives that shaped the draft.